Management of Acute Bleeding from a Peptic Ulcer

N Engl J Med 2008;359:928-37

Priority in Treatment

- Assess hemodynamic status

- Obtain CBC, electrolytes, INR, blood type, and cross-match

- Initiate resuscitation

- Consider NG-tube placement and aspiration

- Perform early endoscopy (within 24 hrs)

- Consider initiating treatment with an iv PPI (80-mg bolus dose plus continuous infusion at 8 mg per hour) while awaiting early endoscopy

- Consider giving a single dose of erythromycin 250 mg iv 30-60 minutes before endoscopy

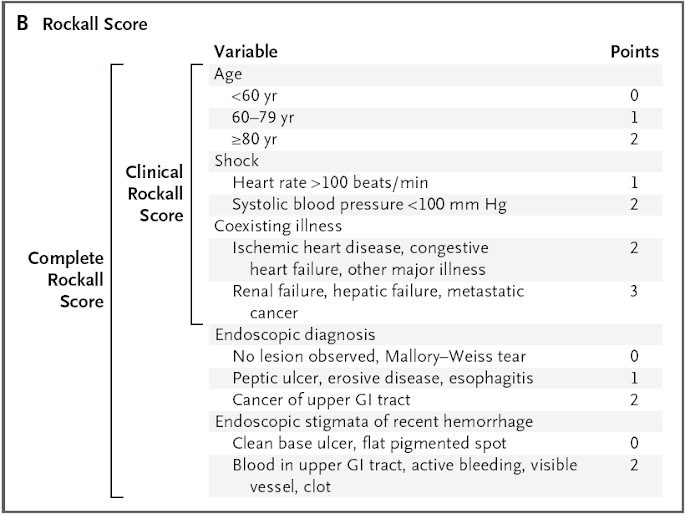

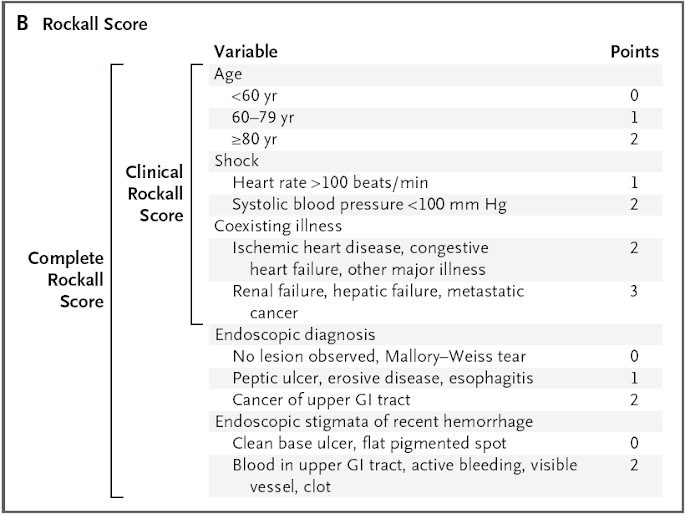

- Perform risk stratification; consider the use of a scoring tool (e.g., Blatchford score or clinical Rockall score) before and (e.g., complete Rockall score) after endoscopy.

Predictors of failure of endoscopic treatment

- history of peptic ulcer disease

- previous ulcer bleeding

- presence of shock at presentation

- active bleeding during endoscopy

- large ulcers (>2 cm in diameter)

- large underlying bleeding vessel (2 mm in diameter)

- ulcers located on the lesser curve of the stomach or on the posterior or superior duodenal bulb

Repeat endoscopy may be considered on recurrent bleeding or if there is uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of hemostasis during the initial treatment.

Surgery remains an effective and safe approach for treating uncontrolled bleeding (i.e., those in whom hemodynamic stabilization cannot be achieved through intravascular volume replacement using crystalloid fluids or blood products) or patients who may not tolerate recurrent or worsening bleeding.

Angiography with TAE is reserved for patients in whom endoscopic therapy has failed, especially if such patients are high-risk surgical candidates.